THE BIRTHPLACE OF GRAND PRIX RACING

For some it’s just a giant granite rock stuck in the middle of the stormy Irish Sea. For many others world-wide it means so much more. A shrine to motorcycle racing for over 100 years. A shrine to grand prix motorcycle racing where it all began 74 years and over 1000 grands prix ago.

It’s wild. It can be windy and wet. It’s certainly dangerous but this is a beautiful place. A mystical magic Island where you can see the mountains of England, Scotland, Wales and Ireland from its highest peak on a clear day. A summit high above the legendary TT mountain circuit on the Isle of Man.

Between the Austrian and Barcelona Grands Prix I paid my annual visit to the Shrine to watch the Manx Grand Prix. It was as it always is. An insight into those pioneering days of World Championship Grand Prix racing around the most famous racetrack in the World. A 60.721 kms road circuit snaking its path through towns, villages, fields, forests and up and down mountains. A ribbon of tarmac diving between stone walls, lamp posts, phone boxes while jumping over bridges and streams.

The TT races go back a long way in history. In 1907 the British government would not close public roads for racing. The Manx government seized the opportunity and closed their roads. The Tourist Trophy races were born, and the rest is history.

Even before you start a lap of the track at the grandstand high above the curving Douglas Bay, you must visit the Fairy Bridge. For over those 100 years the riders have made the trip to ask the fairies in the stream below for a safe race. They have not aways obliged. The famous scoreboard opposite the grandstand that was operated by the local Boy Scouts and had a clock and light indication where each rider was situated on the course, has gone, a scoreboard that had endorsed Freddie Frith as the winner of the very first World Championship race on June 13th, 1949. The scoreboard that told the crowds in 1957 that Scotsman Bob McIntyre had set the first 100 mph (160.9 kph) lap of the mountain circuit riding the 500 cc four-cylinder Gilera.

From the grandstand the riders plunge down Bray Hill between the houses at over 200 kph. They hit the bottom before racing on to Quarter Bridge over the Ago leap. A bump where 15 times World Champion Giacomo Agostini would wheelie those beautiful red 350 and 500 cc MV Augusta fire engines. In my youth I agreed to one lap of the Mountain circuit as a sidecar passenger to double TT winner Trevor Ireson. The first time I opened my eyes was at Quarter Bridge.

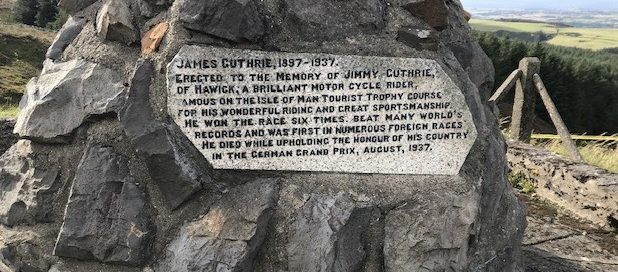

The tarmac then just flows through towns, villages and open roads with mystical romantic names. Union Mills where you can watch the racing in front of the church while receiving wonderful home-made cakes sandwiches and cups of team from the vicar and local ladies. The Highlander, Greeba Castle, Ballacraine and Glen Helen. Onto Sarahs cottage where both Ago and Mike Hailwood crashed on my first visit to the Island in 1965. On through some fast bends such as Rhencullen where the riders travel over four times faster than the 40-mph speed limit signs for normal road uses. Over the Ballaugh Bridge jump on towards Ramsey and the climb up the mountain past the Guthrie memorial. A kiln of stones to celebrate the life of TT winner Jimmy Guthrie who was killed at the Sachsenring in the 1937 German Grand Prix.

Just before the highest part of the course the riders race through the bleak Hailwood Heights, a tribute to the nine times World Champion before plunging back down towards Douglas through bends such as Kates Cottage and Creg-Ny-Baa. The final corner at Governors Bridge passing the front gates of the Governor of the Isle of Man residence.

Every corner can tell a story. Every blade of grass, centimetre of tarmac, stone wall and lamp post has witnessed heroic battles, bitter disappointment and tragedy. Close your eyes and you can touch the very soul of grand prix racing.

It’s a shrine to riders past and present. You have to visit the Isle of Man at least once to understand.